Ilan Manouach: Defamiliarizing Comics

To say that Ilan Manouach is the most recognized avant-garde comics artist in Greece may be faint praise. The country’s independent comics scene—distinct from the world of translated American, western European, and Japanese comics—remains rather small. But Manouach cuts a significant figure even in the world of francophone comics, where the majority of his work has been published. His comics alone are startling in their diversity: densely drawn poetic comics, notorious détournements in the Situationist tradition, and, most recently, a completely unprecedented system of comics for the blind. Additionally, Manouach is an experimental musician and a small-press publisher. Just as his work crosses boundaries, Manouach himself travels frequently to festivals and residences and tours globally as a musician.

Born in 1980, Manouach grew up in a Jewish-Greek family in a suburb of Athens. His mother was a tour guide, his father traveled frequently for work, and the household was polyglot. “French is almost my first language,” Manouach says. As a child he became interested in comics, but “back then there were no Greek comics publishers”; the most commonly available works were translated popular comics from western Europe and the US. He became more aware of ambitious European comics through translations available in a pair of now-defunct Greek comics magazines, Para Pente and Babel, and asked his father to bring him comics whenever he traveled abroad.

“I decided I wanted to study comics when I was like fourteen years old,” he said. After high school he enrolled in the École Saint-Luc in Brussels, Belgium, a school that has since developed a reputation for supporting avant-garde comics education and production. At the time Manouach arrived, Brussels was already an epicenter for a burgeoning movement toward more artistic comics, propounded by the Mokka collective, Fréon (which would become part of Frémok), and La Cinquième Couche, which would later become Manouach’s principal publisher. “The things that I wanted to do back then of course have nothing to do with what I’m doing finally,” he explained. “I was really into [French humor magazine] Fluide Glacial, funny things, until the first year. The second year something made a strange click, I don’t know what changed, and I totally changed my graphic style. And by the third year I already had a very specific proposition of abstract comics, of free-associative images, of a connective space coming from Robert Bresson films. So the three years at school were very big steps into trying to define what I liked in comics.”

Manouach’s development as a comics artist was informed by reading theoretical texts about theater and music. Theater’s dependence on external texts provided a way out of conventional notions of personal expression that existed within independent comics (which at the time heavily privileged autobiography and memoir). Additionally, “music was and is very, very relevant to what I do,” continues Manouach, who has produced a large body of music as part of the experimental improvisatory duo Balinese Beast and the more composition-oriented Glacial. “It gave me the importance of organizing material that would not have naturally come from comics. Free improvisation, for example, advocates for a very egalitarian way of sharing musical space.” Manouach was also influenced by systems theory articulated by Gregory Bateson and the Palo Alto group of the 1950s.

In all their diverse manifestations, Manouach’s comics undercut both the protagonist-based model of classical narrative and the author-expression mode of traditional creative production.

Externalization, improvisation, systems, and collaboration: these ideas and more inform the decentered approach that runs through Manouach’s mature work. In all their diverse manifestations, Manouach’s comics undercut both the protagonist-based model of classical narrative and the author-expression mode of traditional creative production. This was first manifest in his book La mort du cycliste, originally produced as his thesis project and published in 2005 by La Cinquième Couche. The book’s disconnected, free-associative images suggest a poetic exposition but resist diegesis. “It wasn’t important to think that there was a narrative space that was behind the images,” he explains. “I wanted the narrative space to just be something that is created in the mind by having these associative images.” He advanced this proposition in subsequent comics, including FRAG (2007) and Ecologie forcée (2011), which “has a much more mature form of text and image integration and dislocation” and was intended to be read in an installation environment.

In 2009 Manouach began another strand of comics production in the tradition of Situationist détournement, which famously appropriated mass cultural comic strips and replaced banal text with revolutionary messages to become iconic of the student and worker revolts that roiled France in the spring of 1968. “I heard about this work by Carmelo Bene, an Italian poet, theater director, critic, and theater writer, who did a lipogrammatic work on Romeo and Juliet,” Manoauch recalled, citing an Oulipian constraint-based practice of omission. “But he wrote the Shakespeare work by removing Romeo. I never found the play, and I don’t even know if it exists, but I thought the idea was so great and I wanted to do something similar with comics.”

Manouach turned his attention to a volume of Petzi, the French name for a series of innocuous midcentury children’s comics (originally published in Denmark as Rasmus Klump), featuring a cohort of animal characters. Among their number is Riki, a pelican who accompanies the characters in their adventures but never speaks. Manouach proceeded to digitally erase all the characters except Riki from a volume of the series and to alter all the comic’s word balloons so that they pointed to the previously mute pelican character, who now spoke polyvocally, wandering alone in a barren cartoon landscape. Manouach even requested—and received—from the series’ rights-holders permission to publish the project as Riki Fermier. “They didn’t care at all,” Manouach said. “It’s not an offensive work. It’s not a work that created problems. It’s a book that seems like an exercise.”

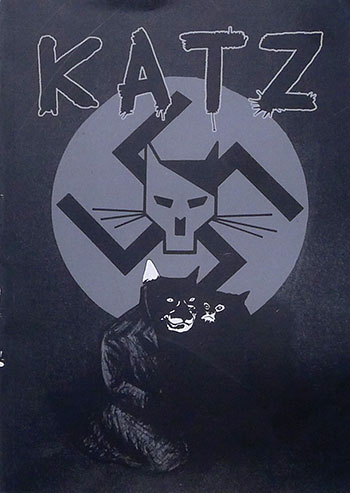

Manouach painstakingly replaced the heads of all the characters in Maus’s nearly three hundred pages with cat heads, investigating the implications of Spiegelman’s approach to representing ethnicity during the Holocaust.

His next détournment—or “rip-off,” as he more bluntly calls them—would be more controversial. Manouach turned his attention to a landmark in global comics culture: Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize–winning graphic novel Maus. “Maus is one of my favorite books,” Manoauch said. “Spiegelman is like Godard in comics. When you are serious in comic books, you have to have him in front of you sooner or later. You have to deal with questions he asks. And I was thinking of how Maus could be a relevant work in 2012. Is it possible to still tell the same old story, even if it’s a very faithful, poignant, and very important personal story?” Manouach addressed Spiegelman’s core representational strategy—depicting Jews as mice and Nazis as cats. “The reasons that I did it were first to give life to Maus and to understand it well, and second in order to question things that have already been questioned regarding this work, this naturalization of the characters that finally promotes a very essentialist reading of history, which is very, very problematic now. And it shouldn’t just be a footnote in Maus; it should be the central focus of the work, this problem.”

Manouach painstakingly replaced the heads of all the characters in Maus’s nearly three hundred pages with cat heads, investigating the implications of Spiegelman’s approach to representing ethnicity during the Holocaust. Further, under the auspices of La Cinquième Couche, he published the complete détourned work, titled Katz, in a small (less than one thousand copies) edition. “The decision to work with Maus should have the same form as Maus itself,” Manouach explained. “It was a book, it should be dealt with in book form.” The book’s timing was auspicious—and provocative. Katz appeared at the 2012 comics festival in Angoulême, where Spiegelman appeared as that year’s special guest of honor to inaugurate a retrospective exhibit. Like all of Manouach’s détourned work, Katz was unsigned in order to preserve the integrity of the appropriated work in every way except for the altered element and thus concentrate the reader’s focus on the work’s sole critical differences. Several independent publishers other than La Cinquième Couche further obscured the book’s origins by selling copies at their booths throughout the festival, and Katz became an underground buzz book at that year’s event.

Manouach painstakingly replaced the heads of all the characters in Maus’s nearly three hundred pages with cat heads, investigating the implications of Spiegelman’s approach to representing ethnicity during the Holocaust. Further, under the auspices of La Cinquième Couche, he published the complete détourned work, titled Katz, in a small (less than one thousand copies) edition. “The decision to work with Maus should have the same form as Maus itself,” Manouach explained. “It was a book, it should be dealt with in book form.” The book’s timing was auspicious—and provocative. Katz appeared at the 2012 comics festival in Angoulême, where Spiegelman appeared as that year’s special guest of honor to inaugurate a retrospective exhibit. Like all of Manouach’s détourned work, Katz was unsigned in order to preserve the integrity of the appropriated work in every way except for the altered element and thus concentrate the reader’s focus on the work’s sole critical differences. Several independent publishers other than La Cinquième Couche further obscured the book’s origins by selling copies at their booths throughout the festival, and Katz became an underground buzz book at that year’s event.

But Katz garnered a different response when Maus’s French publisher, Flammarion, sent a five-hundred-page legal document to La Cinquième Couche summoning the publisher, Manouach, and the book’s distributor to French court for copyright violation. “France has a very different copyright system than Belgium,” Manouach explained, “a much more severe and strict application of copyright law,” and “the costs of participating in trial were very high, around thirty thousand dollars,” well beyond the small, independent publisher’s means. So the parties involved agreed to an out-of-court settlement. The terms: the destruction of all remaining copies of Katz as well as all digital files from which more copies could be produced. The book’s extant print run was shredded in Brussels on March 15, 2012.

But “l’affaire Katz” was not quite over. In 2011 Spiegelman had published MetaMaus, a book about the making of Maus. Manouach and his publisher burned the shredded remnants of Katz and had the ashes mixed into printer’s ink that was then used to publish MetaKatz, a 2013 book about the brief life and destruction of Katz and the issues raised by the experience, including contributions from a variety of artists and critics. MetaKatz “had a lot to say about different things such as resampling in comics, or the history of rip-offs in comics, or the problem of using animal metaphors,” said Manouach. “I think this for me is the prototype of a book form. It’s a book that creates discussion, that creates polemics, and another book that responds to these polemics. I think it’s a perfect example of how I imagine dialectics to be.”

Manouach has continued in this vein, undeterred, taking on projects based on other classic works of comics history. In 2014 he published Les Schtroumpfs Noirs (The Black Smurfs), a détournment of a deeply problematic 1963 book of the same name by Belgian cartoonist Peyo in which a group of Smurfs are struck by an infection that turns them both black and evil. (American editions of the book have sidestepped the book’s racial implications by recoloring the “evil” characters and retitling the work The Purple Smurfs.) Manouach’s edition is identical to the original in every way except that all four of the book’s process color plates (cyan, magenta, yellow, and black) are transferred to the cyan layer, resulting in a confounding monochrome edition that eliminates the visual difference between the good and evil Smurfs (even as the book’s narrative sense is overwhelmed by a sea of blue ink).

In 2015 he published Tintin Akei Kongo, featuring the most iconic character in Franco-Belgian comics. Manouach’s work is based on Tintin creator Hergé’s second story featuring the character, Tintin au Congo (1931). The work is notorious for its racist depiction of Congolese “natives,” which reflect bourgeois colonial attitudes of the time. Even during his lifetime, Hergé and his studio substantially redrew and softened the work, but the book remains problematic (in one of several recent challenges, the book was removed from the children’s section of British bookstore chains after a 2007 lawsuit). Manouach’s edition replicates the current French edition, but for the first time he has had the book translated into Lingala, the official Congolese dialect. In addition to returning this work to the society it has depicted, “adding Lingala to the 112 different translations of the Tintin Empire . . . reveals blind spots in the expansion of the publishing conglomerates.” Moulinsart, the company that has long managed the Tintin trademark, is notoriously litigious. Regarding the legal action surrounding Katz, Manouach admitted that “I wouldn’t like for this to happen again. It was very stressful in the moment. But I was feeling also very optimistic that there are things you can do with comics still. You can still create polemics with comics, you can still create discontent, you can still have discussions about them. I understand that it’s a very politically potent medium, finally. It’s all that I was asking for, to have a medium that was powerful.”

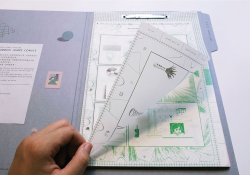

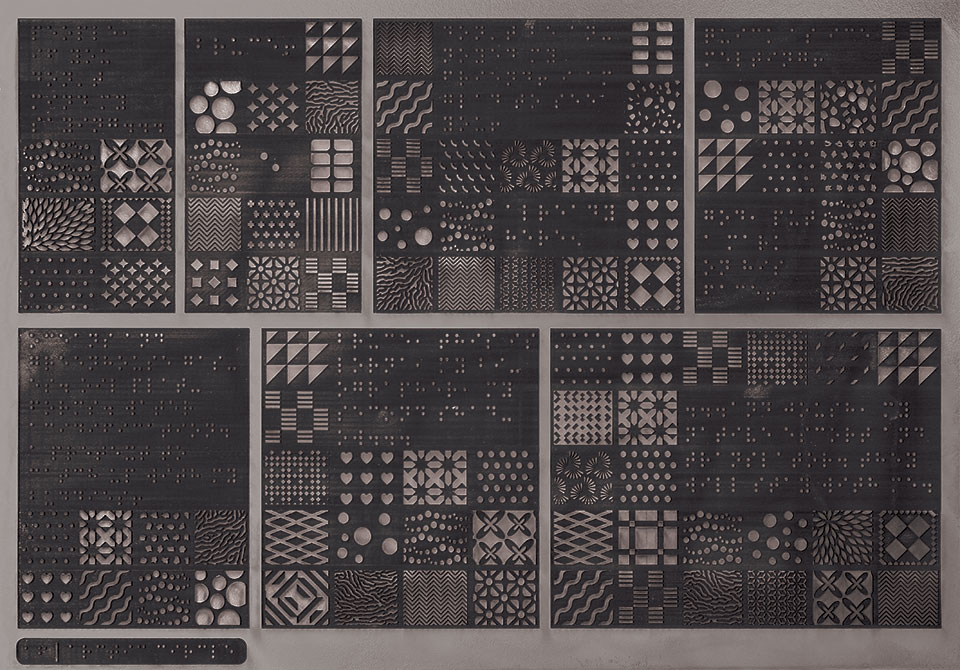

Manouach’s most recent project, Shapereader, extends the power of comics to a previously excluded audience: the blind. “I think comic books are interesting because they are both very material and very immaterial,” Manouach explained. “Comics is a language, a very immaterial thing, but at the same time it’s a very tangible thing. There are books, they take space, they are printed in Singapore, they travel back to the States, they are carried in distribution, sold in bookstores, etc. I wanted to do a work that takes both of these directions and puts them to the extreme.” For Shapereader, Manouach devised a unique system of symbols that designate characters, settings, actions, emotions, and other narrative elements, without recourse either to mimetic pictorialism or to written language (a series of “communication boards” decodes his symbology into standard braille so that the work can be read).

Produced with a grant from the Finnish institution Koneen Säätiö to support multilingualism and art, Manouach produced Arctic Circle, a graphic novel consisting of fifty-seven large (50cm x 35cm) laser-engraved plates utilizing the Shapereader repertoire of forms to tell a story of two scientists researching patterns of climate change at the North Pole. The work is undoubtedly a breakthrough for comics and was exhibited at the 2016 comics festival in Angoulême. Shapereader is also a striking aesthetic object, and Manouach is arranging exhibits in Athens and elsewhere. But he remains most excited by the work’s other possibilities and is developing workshops based on the Shapereader haptic vocabulary. “Shapereader supports a different way of understanding language or experiencing language,” he explains. “My dream is to find other uses for Shapereader that are not in the comics world and probably are not even in the art world.” These include graphic medicine, linguistics, and signaletics. “I want to open this project into different communities. I think if it ends as a comics project, it will kill it. It started from there, but it’s important to go somewhere.”

Throughout all his activities, Manouach remains an energetic, engagé avant-gardist whose work remains unsatisfied with conventional ideas or forms.

At the same time, Manouach is working on a new graphic novel using more traditional media to serve a nontraditional narrative. “I decided on a location for the story, which is an underground cave,” he reveals. “There’s one character who moves around the different chambers of the cave, and she discovers different things. It doesn’t have any climax. It’s different situations that articulate one after the other, probably closer to a kind of meditation or a documentary. I was interested in finding ways to relate to history through very minute details that have to do with mineralogy or animal life.”

In addition, Manouach continues to operate two small publishing houses: Inkpress, which translates North American comics into Greek (an edition of Ben Katchor’s Julius Knipl: Real Estate Photographer is in the works) and Topovoros, which translates radical and experimental texts (from Valerie Solanas to Donna Haraway) for limited distribution in the bohemian and anarchist enclave of Athens’s Exarchia neighborhood. Throughout all his activities, Manouach remains an energetic, engagé avant-gardist whose work remains unsatisfied with conventional ideas or forms. “The artworks I like are artworks that make the familiar unfamiliar, and the unfamiliar familiar,” Manouach explains. This statement sounds very much like a mission statement from this young artist, who will doubtless continue to raise fundamental questions for readers and observers as he moves ever forward in his radical and fascinating work.