Dedications

For Daniel Sada

The dedication was short and impersonal, followed by the unlikely signature: Lauro H. Batallón. Santiago held the copy in his open hand. He seemed to weigh the words of every page, confirming the grammage of the sentences to detect the core of deception.

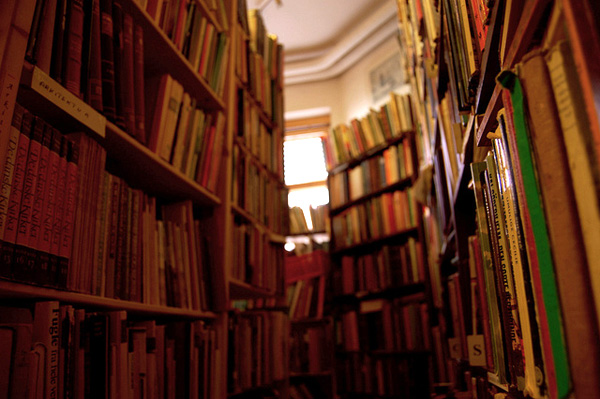

The author didn’t exist; or rather, he had existed, but somewhere in his imagination. Even though he had written each page. A dozen books the same: the smell of old paper, dust, and humidity surrounded him like the aura of a dead man. The hardback copies had lost their shine on the shelves of the Serrera and Amador bookstore, arranged in no particular order. But the copies of The House of the Impossible Widows followed him, the bewitching enigma of the impossible reconstruction of their stories. To whom had they belonged?

My cousin Amador was the orderly one, the bookstore owner used to say. If someone wants perfect classifications, let him go to the library.

In memory of our meeting. With esteem. He outlined mechanically the thick strokes, shifting his vision to what should be the vestige of a plot that he could imagine but never know.

“I was about to put them on the shelves. It’s been a year since you were here,” a reprimand without mistrust. “I didn’t think you were coming back.”

“I wouldn’t do that without saying something, Serrera.”

“Of course.”

The old man had good instincts.

***

One of the dark spines buried on the shelves of La Sulamita bookstore read Sunset over the Barricades. Santiago grabbed the book without thinking, paid for it, and went out outside. He protected it from the rain inside his jacket until he got into a taxi that stopped without being hailed.

He examined the book as he traversed the streets. The buildings seemed to have been built beneath waterfalls. Santiago held the book upside down, looking at the inverted pages as though wanting to alter them, to invent another language.

“How is it?” the driver asked. Santiago shrugged his shoulders. “It looks long.”

Santiago thought about the nineteen hundred and ninety-nine copies of Sunset over the Barricades he still had to locate. How do you recover a book that never belonged to anyone?

***

He entered the café-bookstore Luxemburgo, picked up a book from the table of new titles, and introduced himself to the person in charge as the author.

As soon as the manager saw him, he personally wanted to announce on the intercom that Alberto Matarredonda, the author of The Gods Do Not Roam the Earth, was in the store. There was a photo of the author on the back cover: a beret and sport coat, a pipe and a ring with a green stone on his left hand, an endless beach. Santiago had dyed his beard gray, wore round glasses, and spoke with an affected accent. It all reeked of impersonation.

“Maestro, thank you for your book,” they all repeated.

Conclusion: no one had read the book. It was the author’s literary debut, so it was unlikely that anyone knew two lines of his work. The line was long. People crowded around the table, trying to catch a glimpse of the dedications over his shoulder. When the last person left, the manager invited the apocryphal Matarredonda for a drink in the café.

He excused himself and went to the restroom. He washed his hands and waited five more minutes. As he left, he saw the manager waiting for him in the distance, his back to him. He rushed to the exit; once outside, he began to run.

***

“Can I tell you something, Serrera? I wrote all those books. I was the ghostwriter for a publisher that went out of business years ago but published the complete works of a ghost. One night when we were drunk, the editor and I invented the biography of an author hardened by travels and misfortunes, but saved by literature. It was a lousy joke.”

Santiago said nothing. He looked through the two copies of The House of the Impossible Widows and the copy of Serpentarium, the only crime novel Batallón wrote, its last twenty pages mutilated. At one point, he wanted to write, but he had no desire to be a writer, the celebrity life, the public lectures, cocktail parties, the senseless battles with critics and colleagues.

He agreed to write a novel a year. He wrote the last one, Sunset . . ., when he was thirty-six. He went his own way and didn’t run into Batallón again until ten years later. Santiago entered the secondhand bookstore looking to escape the rain and discovered that the glass door opened onto a past of deception and fear, which had been the cause of his indifference: being exposed, naked, and confessed in the presence of others. What had begun as a joke—passing himself off as unknown writers, signing autographs—led to a day when he still longed for the fame that the pseudonyms had denied him.

“They’re ninety pesos.”

What was the original price? How much value had they lost every year?

“I’ll take any others that come in. I’ll be back in a month or two.”

“We may not be here. My cousin insists on closing the store. He says that one of these days all this old paper is going to fall on top of us.”

Santiago listened to Serrera talk about his partner as if he hadn’t died years ago. He could see through the windows’ reversed letters that it was about to rain. Everything’s precarious, he thought. He left without saying anything. Perhaps a boy had dedicated Batallón’s novel to his girlfriend as a mere game. Perhaps someone else had the same deceitful need to say hello with someone else’s book. He looked back. The drops began to wash away the letters of the bookstore’s display window. It seemed that the vanishing letters did justice to a place not just where used books piled up, but where the past became an incomprehensible knot, a labyrinth with too many dead ends.

Translation from the Spanish

By George Henson