A Day That Lingers with Us Still

Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here

For more, see the gallery of [node:674 title"Al-Mutanabbi Street Broadsides"].

In March 2007 a car-bomb suicide attack destroyed the entire perimeter of Al-Mutanabbi Street, the heart and soul of Baghdad’s intellectual and cultural community for centuries. Responding to this tragedy, artists from all over the world have come to share a sense of solidarity as well as ownership in a project that refuses to let that day, and its significance, ever be forgotten.

In March 2010, after reading a group of poems from the as-yet-unpublished Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here anthology at a poetry festival in Washington, D.C., members of the audience enthusiastically raised their hands and offered their comments about the power of poetry to witness and offer healing from war and violence. After several comments, a young Arab man stood up without raising his hand and began to speak in a shaky voice, thick with an Arab accent. “I was there,” he said, his voice pregnant with held-back tears. “I was on Mutanabbi Street the day it was bombed.” A heavy silence filled the room, and it felt as if a small bomb went off. I could feel each person wanting to duck and take cover from the emotional pain this young man’s simple statement unleashed. With all eyes on him, he continued to narrate: “The stationery store on Al-Mutanabbi where I worked exploded in flames, and my boss was immediately killed. How I survived, I do not know. I lay in the stockroom and could smell the books and newspapers burning. I could taste the smell of burning hair and flesh on my tongue. Lying on the ground, I watched the entire street turn hot and black with smoke and then, after a few minutes, stared up at the hole in the roof and saw thousands of small gray ashes—pieces of paper, books, newspapers—floating down from the sky.”

I stood at the microphone on a stage far from him but felt paralyzed by the scene he described. We were all on Al-Mutanabbi Street at that moment. “Thank you for what you are doing,” he said. “I will never forget that day. It changed us, changed my country forever.”

Like many Americans, and thousands of writers around the world who stood by and watched helplessly as the U.S. invasion of Iraq began on that fateful day in March 2003, I had struggled to make sense of and grasp the destruction heaped upon that nation as a result of this war. Although the official reasons (Saddam’s so-called “weapons of mass destruction”) for the U.S. involvement in Iraq had largely been discredited by 2010, it also seemed everyone had forgotten about the war, forgotten about Iraq and its people. But that afternoon in Washington, D.C., seven years after the war began, those of us in the room at Busboys and Poets lived the moment with Mousa al-Naseri. I understood the profound importance of Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here and why I had become involved with this project. Even now, after President Obama declared the eight-year American war officially “over” in October 2011, the lingering economic, political, and psychological effects of it continue to take their toll. How could it be otherwise? I have never forgotten this man and his vivid description of that day. It lingers with me still. An essay by Mousa al-Naseri, on his connection to Al-Mutanabbi Street, is now included in the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here anthology.

At the height of my own sense of helplessness at understanding the destruction that the U.S. invasion and occupation unleashed, I found a voice in the Al-Mutanabbi Street Coalition in the summer of 2007. Like the founder of this coalition, Beau Beausoleil, I vividly remember reading the news headlines in the New York Times about the bombing on March 5, 2007. The car bomb, which was a suicide attack, destroyed the entire perimeter of one of Baghdad’s oldest and most revered neighborhoods, Al-Mutanabbi Street. Thirty people were killed, and more than one hundred were injured. Although the loss of life was in itself devastating, the symbolism of the street was not lost on Iraqis. Al-Mutanabbi was the heart and soul of Baghdad’s intellectual and cultural community for centuries, and despite years of dictatorship and repression, it remained the place where all Iraqi writers and books could breathe in an atmosphere of relative freedom and human exchange. The stores and stalls that lined Al-Mutanabbi composed a physical world of words and paper where people could buy, sell, and trade books (new and used) freely (and sometimes clandestinely) and traffic in the world of ideas, regardless of how threatening or radical they may have been to the government. To many Iraqis, Al-Mutanabbi Street was much more than a neighborhood, more than its shops; it was an intellectual capital for Iraq. Poets, writers, intellectuals, and political dissidents gathered in local cafés and bookstores to share magazines and books and to debate and discuss politics and culture about the entire Arab world. It was the place that Iraqis frequented during some of the most tense and difficult periods in recent Iraqi history, including the years of the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88), the long years of U.S. sanctions that brought devastating shortages (1990–2003), and before and after the fall of Saddam Hussein and the arrival of U.S. troops.

Al-Mutanabbi Street’s name honors the much-beloved and revered tenth-century Iraqi poet Abu at-Tayyib Ahmad ibn al-Husayn al-Mutanabbi, whose poetry is still recited throughout the Arab world. Al-Mutanabbi himself died in 945 because of some lines in a poem he wrote that caused insult. The injured man sought to end al-Mutanabbi’s writing career, despite his popularity at the time. That a street in Baghdad had survived centuries of warfare, political abuse, and dictatorship made it all the more significant when the car bomb devastated the area and the entire neighborhood erupted into flames.

Enter Beau Beausoleil: a San Francisco bookseller, poet, and community activist for whom the assault on Al-Mutanabbi Street touched a deep nerve. As a bookseller himself and a purveyor of ideas and culture, the bombing of Al-Mutanabbi became a way for Beausoleil to see, feel, and experience an otherwise alienating and distant spectacle of daily news headlines about Iraq. “I was angry every time I read the newspaper,” Beausoleil said, “and I didn’t know what to do.” But the day of the bombing, Beausoleil felt the connection as a bookseller who regards art, words, and ideas as the measure of any society’s humanity and resilience. The bombing thrust itself into Beausoleil’s consciousness, and he knew that he had to respond. Shortly after the bombing, Beausoleil summoned all his connections with writers, poets, and community activists and organized a memorial reading for the Al-Mutanabbi victims because, he said, “That could have been me on that street, watching my life and work go up in ash and flame. It was an assault on culture and ideas which belong to us all.”

It was at that first memorial reading in August 2007 where I encountered the call to action on the poster:

We are among the pages of every book that was shredded and burned and covered with flesh and blood that day.

And to those who would manufacture hate with the tools of language . . .

Those who would take away the rights and dignity of a people with the very same words that guarantee them . . .

And to anyone who would view the bodies on Mutanabbi Street as a way to narrow the future into one book . . .

We say, as poets, writers, artists, booksellers, printers and readers,

That Mutanabbi Street starts here.

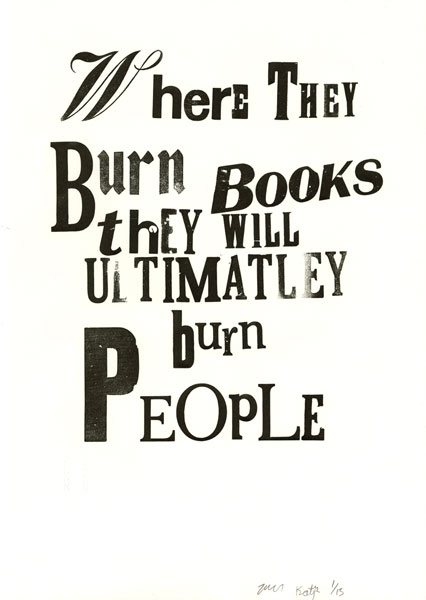

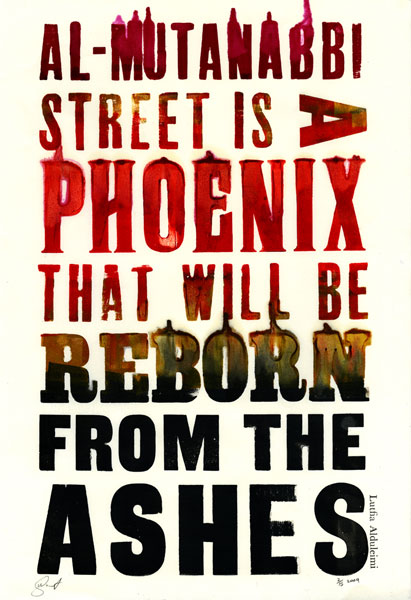

After the reading, I introduced myself to Beausoleil, and like many others, I was inspired to participate in what would later be called the Al-Mutanabbi Street Coalition. What started as a call for poets and writers to write and read poems in April 2007 in memory of those who lost their lives on Al-Mutanabbi Street quickly morphed into a call to letterpress printers to produce a visual response to the attack. The response Beausoleil received was immediate and overwhelming, with over forty letterpress printers responding with powerful and evocative broadsides based on their responses to the bombing or incorporating poems written about the war or the Al-Mutanabbi bombing itself.

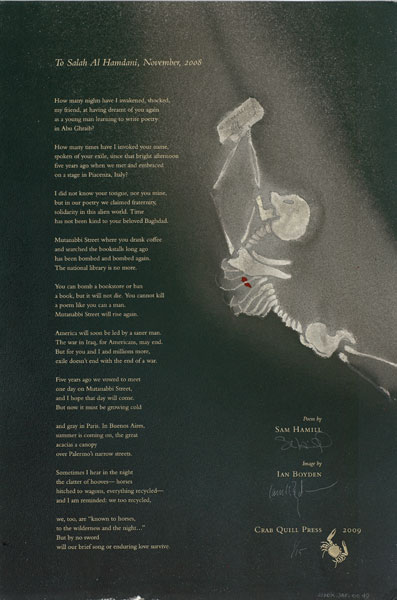

Several months later, Beausoleil invited me to submit my own poem about the war in Iraq, “Ways to Count the Dead,” which would later find its way into the hands of Florida letterpress printer Jill Hearne. When I opened the box nearly six months later and found the most beautiful and visual representation of my poem, which had become a homage to the incalculable loss of life—with hatch marks embossed on the paper—I was moved to tears. When I called up Hearne to thank her for her beautiful work, for returning my poem to me and making it her own, she told me how working on the broadside had affected her. She described the painstaking process by which each of the hundred broadsides was printed five separate times to achieve each of the colors, textures, and fonts. “Working on making your poem come alive on the broadside,” she told me, “over and over, each time moving it through the press, was like a meditation for me. I became intimate with the poem’s language and form, its quiet recognition of loss. I felt the poem in a new way. I felt a connection to Iraq.”

Many of the now 133 broadsides are breathtakingly beautiful and have incorporated lines from the poet al-Mutanabbi’s verse or poems by contemporary Iraqi and American poets. The entire collection of these broadsides is now digitized and available at Florida Atlantic University’s Jaffe Center for Book Arts website (www.library.fau.edu).

The reading I attended in 2007 at the San Francisco Public Library was the first of many memorial readings still held around the country every March in cities like Boston, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C. Since 2010, cities in Europe—London and Dublin—have also hosted readings, and Amsterdam hosted an exhibit of some of the broadsides. Since that first reading, Beausoleil has hosted his own memorial reading around the anniversary of the Al-Mutanabbi bombing in his cozy, two-story Great Overland Book Company in San Francisco; each time he shares more about the dynamic and powerful project that includes local and nationally celebrated poets and writers from around the world.

The Al-Mutanabbi Street Coalition has now evolved and morphed into an organization—if you can call it that, since it operates loosely by a kind of goodwill-based and largely independent coalition of 450 book lovers, artists, letterpress printers, book artists, and cultural workers from twenty-one countries, some of whom live in Iraq. They have come to this project with the vision that Beausoleil brought to it originally: to respond, reflect, and express through art a much larger and human connection to others who have been rendered voiceless by war and violence. The coalition has moved beyond its early mission to respond to a single, indelibly notorious day of death and destruction, into a cultural initiative that celebrates words, books, ideas, and the way they connect us. The coalition, which now goes by Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here, has evolved since 2007 to include four areas: (1) the collection of more than 133 broadsides, many of which have traveled around the world in exhibitions and have been sold to raise money for Doctors Without Borders; (2) an anthology of poems and essays, Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here, edited by Beau Beausoleil and Palestinian American poet Deema Shehabi, which features the writing of Iraqi, American, and other international poets and writers in response to the bombing (forthcoming in June 2012 from PM Press); (3) a collection of over 262 handmade books by artists that “hold both the memory and the future of the Al-Mutanabbi Street bombing”; and (4) readings, exhibitions, and cultural events that continually emphasize, long after the bombing, the important role that cultural centers and spaces of literary and intellectual encounter play in our lives. Exhibits of the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here broadsides have been shown in universities, galleries, and state institutions and museums such as Gallery 31, which is associated with the Corcoran School of Art and Design in Washington, D.C.

More than the actual poems, books, readings, and broadsides themselves, the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here project reflects the powerful processes by which an idea born from one person’s urgency of feeling becomes a collective conversation around which artists from all over the world feel a sense of solidarity as well as ownership. The project has enlisted some of the finest poets for the collection, including its co-editor, Palestinian American poet Deema Shehabi, who first heard about the project from the Iraqi-Canadian poet Zaid Shlah. Shehabi writes:

The project appealed to me because Beau’s primary vision creates a “clearing” of sorts; this clearing has become a space for memories, for grieving, for acknowledging our human commonalities through shared histories of violence, and, ultimately, for regeneration. I am only now beginning to understand how regeneration from destruction is so embedded in Iraq’s cultural ethos. By building these connections through the written word, the project has been immensely successful in creating a deep cultural literacy, a literacy that will resonate for years to come. For me, the project remains in its essence about upholding the Iraqi cultural community’s steadfastness in the face of destruction.

In addition to asking individual poets to invite other poets to contribute to the anthology (serving as kind of section editor), Beausoleil has recruited a number of dynamic and energetic artists, including Sara Bodman from the Center for Fine Print Research (cfpr) in the UK, to co-curate An Inventory of Al-Mutanabbi Street, a project to “reassemble” some of the “inventory” of reading material that was lost in the car bombing. Bodman has helped contact artists, organize exhibits, and get the word out about the project in Europe (to view some of the Al-Mutanabbi books, see www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk). Eventually, when the project is completed in fall 2012, a complete set of 262 books will exhibit worldwide in 2013–14 and then be sent as a gift to the Iraqi National Library in 2015.

Although the project has changed from its early idea of “witnessing” the tragic event of the bombing on March 5, 2007, Beausoleil says the core of Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here continues to be the idea of bearing witness and not turning away. “We are not just antiwar,” says Beausoleil. “We are not looking for healing, per se, but instead to confront a truth. I don’t want people to see the broadsides, the books, or the anthology in a passive way, but to create an opportunity to look at and confront a truth of which we are a part. It is a project that asks something of its viewer.”

At the most recent commemorative reading in San Francisco on March 2, Beausoleil paid a special tribute to American journalist Anthony Shadid, who had covered the war in Iraq throughout the past decade and died in February while on assignment in Syria (see WLT, March 2012, 50–55). Beausoleil spoke of the ways that Shadid had championed the Al-Mutanabbi Street project and put him in touch with the director of the Iraqi National Library. Beausoleil’s ultimate vision for this project is to someday return the books, broadsides, and anthology to the Baghdad library so that Iraqis themselves can see them and know they were not completely alone and that others understood their suffering. “It is my dream to go to Baghdad and present these broadsides and books to the Iraqi National Library and then sit down at the rebuilt Shabandar café on Al-Mutanabbi Street and speak with the writers and poets who frequent this neighborhood,” he says.

A few days after this most recent reading, I received an email from Beausoleil in which he described the giddiness he felt at receiving an Iraqi news article written by novelist Lutfiya Al-Duleimi (one of the Al-Mutanabbi Street contributors in Baghdad). She had written an article for a large Iraqi newspaper marking the fifth anniversary of the bombing and describing the ceremony on Al-Mutanabbi Street that honored relatives of those who died as well as survivors of the blast. “She didn’t just report on that moving gathering on Al-Mutanabbi Street,” wrote Beausoleil. “She also wrote about our project and pasted in broadsides and two of the artists’ books (Anna Wexler and Donna Ruff) into the article. This is the first time that this project has been discussed in an Iraqi newspaper. I can’t tell you how happy this makes me to know that the Iraqi people are becoming aware of what we are trying to do!”

To have this project reach back to Baghdad and to Al-Mutanabbi Street is one of the goals that Beausoleil envisions for this project, which now relies on the energy, vision, and interest of its many “members,” who live in places as diverse and far away as San Francisco, Amsterdam, Baghdad, Omaha, and Santa Fe, and who, despite the short memory that most Americans have of the long war in Iraq, refuse to let that day on Al-Mutanabbi Street, and its significance, ever be forgotten.

San Jose, California