Editor’s Note

One of the characteristics that binds Indian literatures and begins to define a canon distinct from others is a belief in the primacy and potency of the word and utterance. —Rodney Simard (Cherokee), World Literature Today, Spring 1992

IN HER GUEST EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION to the “After Alcatraz” issue of WLT, dedicated to literary activism, Allison Hedge Coke refers to the “long lineages of active presence, of resistance, in the long, long continent of the Western Hemisphere” represented by more than 20,000 years of Native inhabitation (“An Active Measure,” Autumn 2019). Given the current issue’s focus on the Indigenous literatures of the Americas, the editors wanted to represent as much of this “long, long continent” as possible.

IN HER GUEST EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION to the “After Alcatraz” issue of WLT, dedicated to literary activism, Allison Hedge Coke refers to the “long lineages of active presence, of resistance, in the long, long continent of the Western Hemisphere” represented by more than 20,000 years of Native inhabitation (“An Active Measure,” Autumn 2019). Given the current issue’s focus on the Indigenous literatures of the Americas, the editors wanted to represent as much of this “long, long continent” as possible.

Beginning from our base in Oklahoma, the cover feature opens with an interview highlighting the work of Kiowa/Cherokee/Mexican writer Oscar Hokeah. In discussing his acclaimed debut novel, Calling for a Blanket Dance, Hokeah frames it as a “decolonization narrative” while reminding readers that “when we in the United States think of Native Americans, we think of United States Indigenous and Aboriginal peoples in Canada, but Mexico and Central America are filled with Indigenous communities.” That decolonial stance is most vividly on display in the emphasis on Native languages throughout the section. ʻŌiwi poet and educator No’u Revilla foregrounds ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi words and concepts in her essay “How to Swallow a Colonizer,” and many of the poems featured here can be read—and listened to—in bi- and trilingual versions either in the print edition or on the WLT website.

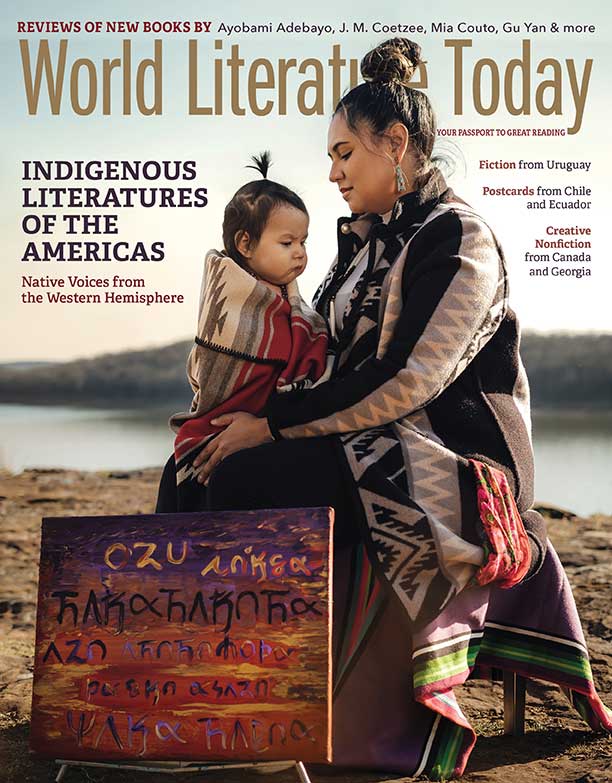

A case in point is Chelsea T. Hicks’s “ie wa^thakika^ ko^bra i want you to help us talk,” her bilingual poem in Osage and English, which is presented in Wahzhazhe ie orthography. Moreover, Hicks’s striking photography project of collaborative visual poems called Waleze also graces the cover of the issue and the opening pages of the special section by incorporating Osage-language painted poems in the photographs. The photographs are not just aesthetically beautiful: the final line of the poem by Mary Hammer on the cover of the issue, “No one cries alone with me,” encapsulates Hammer’s activism as an advocate for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women.

In terms of the broader scope of decolonization, efforts to revitalize Native languages are central to that project. According to the Language Conservancy, “the voices of more than 7,000 languages resound across our planet every moment, but about 2,900 or 41 percent are endangered. At current rates, about 90 percent of all languages will become extinct in the next hundred years” (languageconservancy.org). The most striking visual representation of language loss can be found in a series of maps on the Conservancy’s website that depict much of the world in shades of green in 1920, with the United States and Australia conspicuously yellow. Over the course of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, those greens and yellows shade into oranges and reds as boarding schools and government policies, especially in the United States, Canada, and Australia, “aimed to strip peoples” of their languages and, with them, their cultural identity. As Malintzin (La Malinche) and Sacajawea experienced firsthand, “Siempre la lengua fue compañera del imperio” (language was always the handmaiden of empire), in the words of Spanish grammarian Antonio de Nebrija. Undoing empire is also a linguistic project, often a gendered one.

In an essay that accompanies her translations and co-translations of a number of Mexican and Guatemalan poets, Wendy Call describes this reclamation project as one of “emancipatory activism.” We hope that the sampling of fiction, essays, and poetry included in this issue’s cover feature will inspire readers to learn more about the linguistic, cultural, and political stakes embodied in the work of those Native writers presented here—and to seek out many more Indigenous voices from this “long, long continent.”

Daniel Simon

I would like to thank my faculty colleagues Kimberly Gail (Méona’hané’e) Wieser-Weryackwe, Tana Fitzpatrick, Carol Rose Little, and Jake Skeets in helping conceptualize and curate this issue’s cover feature. Thanks as well to America Meredith, editor of First American Art magazine, for her guidance in recommending artists to illustrate it.