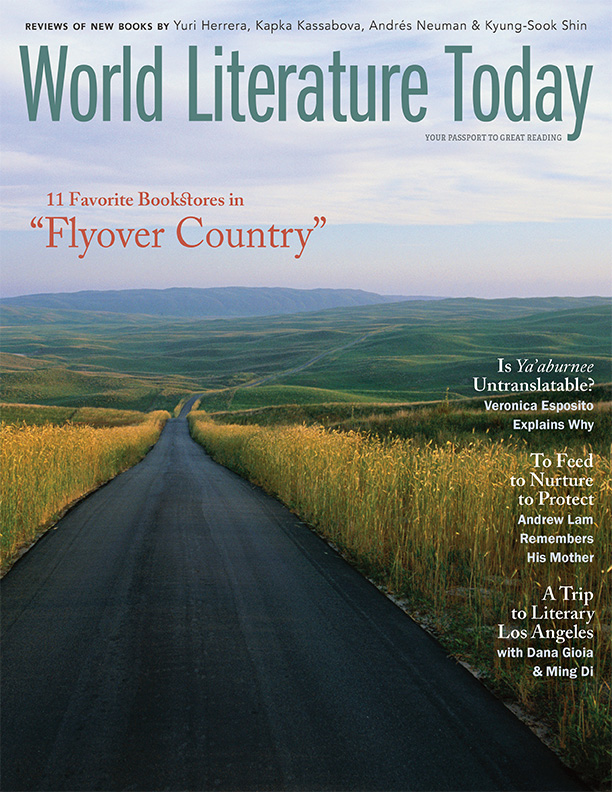

The War on Memory in Russia Today: A Conversation with Irina Flige

In April 2023 Irina Flige—director of the Research and Information Center “Memorial” in St. Petersburg, Russia, and a longtime board member of Memorial International in Moscow—visited the University of Oklahoma to receive the Clyde Snow Social Justice Award. The following interview was conducted during Flige’s visit. In it, Flige speaks about the current situation of the Memorial human rights network. Although the Putin state closed several key Memorial organizations in 2021, including International Memorial and the Memorial Human Rights Center in Moscow, other Memorial organizations in Russia and abroad remain active. In 2022 Russia’s Memorial network as a whole shared the Nobel Peace Prize with the activist Ales Bialiatski from Belarus and the Center for Civil Liberties, a Ukrainian human rights organization.

The Clyde Snow Social Justice Award honors the memory of the pioneering forensic anthropologist Clyde Collins Snow (1928–2014), who used his skills to help identify victims of political violence found in mass graves following the Latin American dirty wars of the 1970s and 1980s. For more on Snow and the award, see OU’s Center for Social Justice website.

Emily Johnson: Can you speak a little about human rights work in Russia today? How has the situation evolved since the closure of International Memorial in 2021?

Irina Flige: International Memorial—and particularly the Human Rights Center Memorial in Moscow—played key roles in the defense of human rights in Russia, and other forms of human rights activism grew up around them. In that sense, the closure of the legal entity International Memorial and of the second legal entity, the Human Rights Center Memorial, complicated our work. Nevertheless, it is important to understand that Memorial is not just an organization—it is a group of people, and you cannot close people.

I can’t say that everything has remained as it was. Part of our work has become even more vital; some of our activities have been transferred to other countries. After all, International Memorial was designated as “international” for a reason. It was a collaboration between organizations based in a variety of countries—the Czech Republic, Italy, France, Poland, Germany, Ukraine—and was a union of independent organizations, just as the Memorial network unites independent organizations within Russia. Of course, some of my Memorial colleagues in Moscow have had to leave Russia for Europe because of threats to their safety. Memorial staff from the provinces have also left in some cases. Nonetheless, in Russia itself, the work goes on. It continues in Moscow and, of course, in Petersburg, and also in other cities in Russia.

In some places Memorial has been liquidated as a legal entity. In others, the local organization retains its status. In Petersburg, our organization retains its status as a legal entity, we still have a bank account, and we are working, generally, on a legally sanctioned basis.

Johnson: Can you talk a little about the position of Memorial’s staff today? I know the apartments of a number of Memorial staff members in Moscow were searched in March.

Flige: At the very beginning of March, we learned that an unidentified group of individuals were being investigated for “the rehabilitation of Nazism.” This formulation—which was introduced into the Russian legal code a few years ago—is really contemptible, because even a conversation about the Katyn massacre [of 22,000 Polish officers and other Polish prisoners in 1940 by the Soviet secret police] can be viewed as the rehabilitation of Nazism—in their [the authorities’] conception, of course. This is how the statute is being applied in practice. This charge could also be applied to a discussion of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. From the point of view of Putinist ideology, such a discussion would reflect an unpatriotic perspective and hence the rehabilitation of Nazism.

Our enormous Memorial composite database, which lists victims of the Soviet terror, is another example of something that can lead to charges of rehabilitation of Nazism. Article 58 of the Soviet legal code [covering counterrevolutionary activity, treason, espionage, and terrorist acts and used to sentence political prisoners] was in use before, during, and after the war [World War II], and some people were convicted under it for collaboration on formerly occupied territory. We have no way to determine what percentage of these convictions were falsified, and how many were real cases in which people participated, for example, in Nazi campaigns such as mass shootings of the Jews. Until you examine the case file, you have no way of knowing how to evaluate a particular case.

Our enormous Memorial composite database, which lists victims of the Soviet terror, is another example of something that can lead to charges of rehabilitation of Nazism.

The law on rehabilitation [of victims of political repression] is just as arbitrary in its application as the terror was itself. The essence of this law—at least in its practical application—is that anyone convicted under article 58 is generally rehabilitated. As a rule, those convicted under other articles are not rehabilitated. For this reason, some of the people who were convicted for collaborating—they had this article 58 conviction, and they were rehabilitated by Russian procuracy and ended up in regional volumes listing victims of the terror. Therefore, they are also listed in Memorial’s composite database [which pulls together all the names in regional Memorial volumes]. These are people whose biographies have not been studied. And so, some veterans found two or three individuals out of the 3.5 million names in our database—all of whom had been rehabilitated by Russian procuracy—and said that Memorial was fascist. We do not know how many cases they [the authorities] are pursuing. Maybe it is all about the people they found in the database, these patriots, or maybe there are additional charges based on lectures and publications on the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The law [on the rеhabilitation of Nazism] prohibits comparisons between Nazism and Stalinism, and, of course, what is the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact? It is when these two evildoers [Hitler and Stalin] came together and took coordinated action.

So, this criminal case has been launched. We knew this was happening, but the individuals being targeted remained unidentified. In connection with this, in March, the homes of nine Memorial staff members and two offices in Moscow were searched. The offices were just ransacked. It wasn’t even a real search. In the homes of the staff members, what took place was partly a search and partly just ransacking. The law-enforcement officers we have now, they just take a cabinet and dump everything in it on the floor. They confiscate all the technology. Sometimes they take some of the documents and books, but the technology is the main thing: telephones, portable hard drives, flash drives, tablets.

At the same time [March 2023], a case was also launched against Oleg Orlov [chairman of the board of the Human Rights Center Memorial] for his antiwar texts and speeches. Last year he protested on Red Square and in other places in Moscow with signs reading “Say no to war” and “the Putin regime is a fascist dictatorship.” He was charged and assessed fines for his participation in public demonstrations. These were just administrative sanctions. But when there is one administrative sanction after another, then the next step is a criminal case. And so, at the same time as the searches were taking place, Orlov was criminally charged—the formulation that is used sounds almost comical—for “fake news.” Really, he was charged in connection with his antiwar position. Right now, the article he is being charged under is relatively light and can lead to sentences of up to five years of imprisonment. There are more severe articles, such as the one that Kara-Murza [Vladimir Kara-Murza, a prominent political activist and journalist who received a twenty-five-year sentence in April 2023] was convicted under. But these articles are very similar, and the charges can be changed at any time.

Johnson: In other Russian cities—for example, in the provinces—are Memorial staff and affiliates facing equivalent pressures?

Flige: It is hard to say unequivocally. In some places such as Perm, things were very bad and remain bad to the present day. Formally, Memorial in Perm was connected to International Memorial, not as an independent organization but rather as a subsidiary branch. For that reason, when International Memorial was closed, Perm Memorial was automatically liquidated. We—Petersburg, Ryazan, Tomsk, and all the other cities—were all members [of International Memorial], which means that when International Memorial was liquidated, we just did not have a larger structure to link us all together. But we are independent organizations. We have our own charters, our own registration. In Perm—things just developed this way historically—they were always a branch of International Memorial. International Memorial had several such branches; Memorial in France was one. This was [because of] a legal requirement: international organizations were expected to have several subsidiary branches. For that reason, French Memorial, Czech Memorial, and Ukrainian Memorial were structured this way. In Russia, there was only one such branch, and that was Perm. Of course, in France, the Czech Republic, and even more so Ukraine, Memorial did not suffer, but Memorial in Perm was automatically liquidated just because of the decision of the court.

Of course, our people in Perm created another organization. Everyone understood what was likely to happen, so they had time; they could prepare and create a new organization. But, since there was direct pressure from Moscow, the authorities began taking repressive measures. Several people from Perm had to get out of the country very quickly.

So, in Perm things were very severe. In Ryazan, things are quiet; in Krasnoiarsk, things are quiet. So, it has really varied. It has been interesting for us too [in St. Petersburg]. We were declared foreign agents. We were really all deemed agents, so that is not significant. What is significant is that we have been subjected to continuous reviews. A review by the procuracy was launched in the beginning of October 2022. We still do not know the resolution.

Johnson: I know that you played a key role in locating and memorializing the Sandarmokh killing fields in northern Russia, where thousands of victims of Stalinist terror were executed. Can you talk a little about what is happening now with this site?

As is the case everywhere in Russia now, a kind of war of memory is taking place in the Sandarmokh killing fields.

Flige: Well, as is the case everywhere in Russia now, a kind of war of memory is taking place there. Before the beginning of the war with Ukraine—and we think of that as beginning with the seizure of Crimea—it was a wonderful site. The administration of Karelia, various officials, and delegations from a whole variety of countries came, and we conducted simple, very eloquent days of remembrance, at which the formula we used was as follows: “Here in mass graves lie people of various confessions and nationalities,” and so forth. Moreover, August 5 in Sandarmokh was the only international day of remembrance. Other attempts [to create such a day] did not take hold. The Poles tried to create an international day of remembrance for the victims of communism and fascism, but it did not take hold. I am really talking about Russia: it did not work in Russia. It [our day in Sandarmokh] is the only one that really worked. If we turn to the Day of Remembrance for Political Prisoners on October 30, it does take place and is observed in a variety of regions, but it is completely regional: “We have come here today to remember our city residents who died . . .” and so forth. But an international day dedicated to the tragedy of that regime [the Soviet Union] as a whole, such a thing existed only at Sandarmokh. Everyone came. Memorial people wrote the program; everyone spoke. They said what they wanted; there were no limits.

For the first time, the Ukrainian delegation did not come in 2014. The officials were all still there, by the way. And for the first time there were serious references to how the ceremony spoke to current realities. I spoke. Dmitriev spoke [a prominent local historian and activist in Karelia]. It just hung it the air. You know, it was as though the absence of the Ukrainian bus left an empty place. In 2015 people didn’t have the opportunity to speak, and in 2016 [the administration of] Karelia completely refused to participate. I led the meeting with my voice and no amplification—there was no radio machine or microphone. We had not prepared. Dmitriev did too. But then, in 2016, Dmitriev was arrested.

In later years it got better again. They [the officials] weren’t around anymore. We came, and we knew that there wouldn’t be any microphones, so we brought them with us. Even more people came than before. Then there was the pandemic. In 2020 more than one hundred people came despite the pandemic and everything being closed. And so it went. Last year, more than three hundred people managed to get there. It is not that easy to get to Sandarmokh. The site is nineteen kilometers from Medvezhegorsk, a very small place of settlement by Russian standards.

The sense of solidarity [that we feel at Sandarmokh] is not about the past. It is solidarity in connection with what is going on now. It is about support for Dmitriev, for other political prisoners. People arrive with these stacks of postcards, which those gathered use to draft messages to political prisoners right in the forest, holding the cards against their knees as they write. Sometimes the postcards are made from photos of Sandarmokh. Support groups collect money, buy the cards, give them out, and ask everyone to sign them. And then, just so that people do not forget to drop them in mailboxes, the support groups even collect the postcards and send them themselves later.

In this same period [starting in 2016], some historians from Karelia got in touch with a military-historical society and decided to find some Red Army soldiers who had died in Finnish concentration camps and [who], they assured people, were buried at Sandarmokh. It is really interesting, though. At the same time, they did not deny that Soviet victims were buried there. But they claimed that the Finns had also conducted burials in the very same pits. But we managed to beat back this attack and in the most academic fashion. As soon as they appeared at the site, our observers set off with GPS units and their training in how to describe material artifacts. So, they would dig things up, and our people would stand there with a tape measure and would start checking the depth, would number the pit in which they were digging, and would mark it on the map. Every step they took was documented. I think they probably had this idea that they would place a monument to the Russian soldier at Sandarmokh alongside all the other monuments, and thereby show that things are not so unambiguous and that there were probably Soviet combatants buried there [as well as victims of the Soviet terror]. But, I think, thanks to the brilliant work of our observers, it all fell apart. At least they have gone silent.

Johnson: Do we see equivalent efforts to cover up the history of the Stalinist terror at other former camp, prison, and execution sites in Russia?

Flige: No, probably no. Except for the always painful Katyn—that is, [the executions of the Polish officers that happened] at Mednoe in the Tver region and near Smolensk. Those are open wounds that just will never close. In other regions, memory of the terror does not really bother anyone. It does not interfere with Putinist ideology. It does not bother anyone that there is a monument to the victims of political repression, and then right around the corner, they place a bust of Stalin.

Johnson: But if there are no issues like this in other regions, then why is Sandarmokh such a focus of attention?

Flige: I will explain. There are several reasons. First, what makes Sandarmokh stand out is that it is an international memorial site. Anything international is really an issue. The Poles come to remember their own people, and the Finns theirs. That at least the Russian authorities can tolerate. But when people come from countries that do not have a direct connection to the Soviet terror—America, Japan, . . .—and start laying flowers and say that the Soviet terror is a humanitarian catastrophe that affected the whole world, that is what is called “interference in the internal affairs of Russia.” Intuitively, they [the Russian authorities] have always understood that international memory of the Soviet terror is not a private Russian matter just as—excuse me—the Holocaust is not a private German matter, and the Argentinian terror is not a private Argentine affair. This is our world memory and our world culture. We fight for this, not just for our own country. Now everything is shut down, and neither researchers nor travelers can come to Russia. For this reason, now diplomatic missions attend the day of remembrance in Sandarmokh, and that is like waving a red flag in front of a bull.

International memory of the Soviet terror is not a private Russian matter.

Johnson: How has the war in Ukraine affected Memorial’s work?

Flige: New forms of human rights work have appeared. For the most part they are connected with refugees [and] aiding people who participate in protests. The School of Civic Defenders is really important for us [a civic defender is an advocate, assigned to a prisoner, who may not have a legal degree]. There is a shortage of lawyers. They face pressure and also leave. So, a civic defender is a great thing. This does not all have to happen within Memorial’s network. It can happen in the larger society. You have people who want to become civic defenders. This gives them the right to meet with prisoners and correspond with them outside of regular limits. These rights are sometimes violated, but, still, it is a kind of defense, and, of course, ideally each prisoner would have this kind of civic defender. That is really important. These schools are constantly appearing, because you really need to have a good understanding [of the law to act as a civic defender].

Johnson: What internet projects are you doing right now? I know you have been working on a variety of internet projects for a long time.

Flige: For the past year we have been frantically digitizing our archive. We fervently believe in open archives without registration requirements or limits. That is one of our most important priority ventures. Another is the Necropolis of the Terror, a map of verified sites of mass burial. We have begun to do some very interesting things with some specific [execution and mass burial] sites like Sandarmokh, Levashovo, Krasnyi Bor, Kommunarka [in which we create an online] map of the territory itself, showing all the monuments at the site. We also have established relationships with artists and designers, and they have put together an online exhibit: A Virtual Walk through Sandarmokh. In this virtual walk, you find yourself in a somber forest, you move through it and search for things, and art objects appear as you go.

My favorite project was done with the help of some students. The project is titled Islands of Freedom and Unfreedom. Right now, it just covers Petersburg. It is a map that shows sites where particularly notable protest actions took place. We suggested the students focus on 1917 to the present. Because of that, the map includes—for example—the protest of Boguslavsky on the Anichkov Bridge [where he held up his sign] “Brezhnev, get out of Prague!” He was then arrested, and the site tells of the later fate of this Boguslavsky. Rybakov’s sign on the Peter and Paul Fortress is noted on the map, and the murder of the antifascist Timur Kacharava by the store Bukvoed is also noted. The entries are all different; the students choose them themselves. We give the students basic material to get them started, but then they collect more themselves and perhaps conduct an additional interview [with a participant]. Basically, each entry is a small study of an event.

Johnson: What does it mean to you to be the recipient of the 2022 Clyde Snow Social Justice Award?

Flige: For me, this was very important. It is a great honor, particularly since Clyde Snow himself was involved in the search for the dead. That is very close to my heart. If you look at my scholarly interests, most of my academic work has been on deaths in confinement. I know what wonderful research he did and how he moved this form of anthropological work forward. That is all very important for me. That is one thing. Second, the prize is a great responsibility, because no prize is ever just given for past work. It is given with an eye to the future, to what you will do in the future.

April 2023

Translation from the Russian

Editorial note: Read Flige’s lecture “History as a Battlefield in Putin’s Russia,” which she delivered at the University of Oklahoma in April 2023, from this same issue.