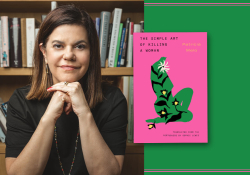

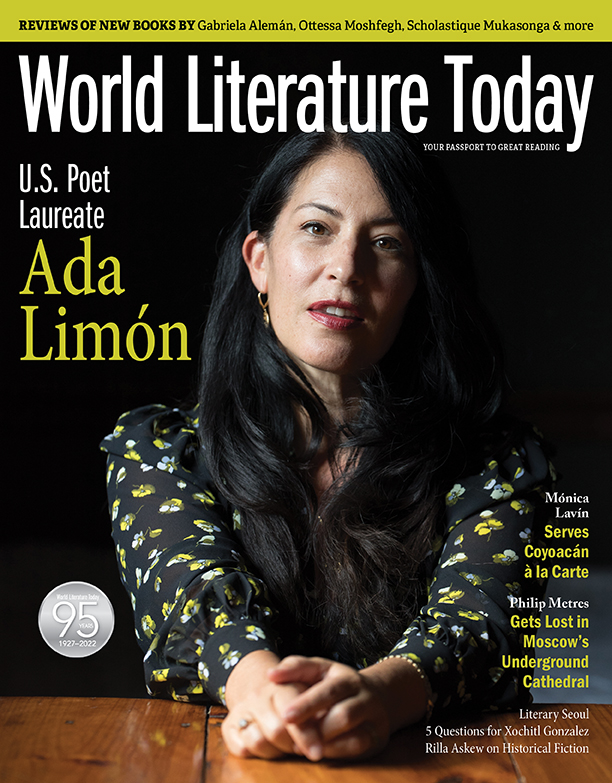

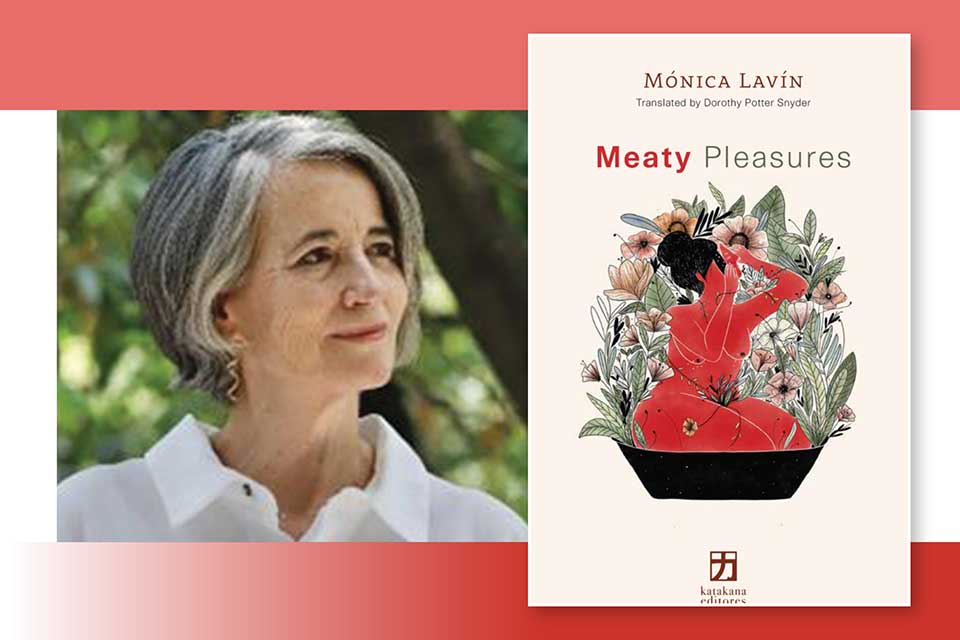

Q&A with Mónica Lavín

Mexican author Mónica Lavín’s first book available in English, Meaty Pleasures, is a collection of twelve stories translated by D. P. Snyder and edited by Michelle Rosen (2021). Snyder writes that she chose the stories “that left the deepest mark on me for their unflinching gaze at human desire and the body.”

Q: D. P. Snyder described your stories as “the most visceral and unabashedly physical tales by a Hispanic woman I had ever read.” Are there other writers who inspired you in this regard, or are you taking sensual writing to a new place?

A: I find the language of the body, the skin, the senses strong and subtle. I like my characters to deal with the unsaid, the eloquence of silence. I bow to Chekhov’s emphasis on atmosphere in “The Kiss,” where the rumble of the cloth is a way to decipher which woman was the carrier of the mistaken kiss. And Carver in his emotional silence. D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Ian McEwan’s On Chesil Beach and of course Marguerite Duras’s The Lover. Inés Arredondo, a Mexican short-story writer in the 1950s, left a mark on me. I like the idea of being related to sensual writing and the weight of atmosphere and silence as a way of revealing internal landscape.

Q: Food is integral to the stories, and you also write nonfiction food pieces. Who are some of your favorite food writers?

A: Food writing in Mexico was strong in the first half of the twentieth century, coming from bewilderment and comprehension of our cultural interbreeding since the Spanish chronicles about the new land. Antonio del Valle Arizpe made the most baroque and sensual descriptions of Mexican sweets on tables and storefronts in his chronicles. Salvador Novo explained the way we eat in Mexico City through an iconic historical review. Much of Mexican history is also told through its tables. I do the same, the way food tells about a period, a family, like the poet-nun Sor Juana. In fact, it was writing about a recipe book found in the San Jerónimo convent where she lived that I got the desire to write about her life. I enjoy the way we use gastronomical metaphors to explain life issues. Appetite is a wonderful word.

Q: Are you a “foodie”? Is there something you love to cook? I’m wondering what the table would look like if you threw a dinner party.

A: My father used to say, when I came back from a trip and shared the highlights, that it seemed like I spent most of my time eating. I realize now that it is an important motive for my moving around, a way of exploring invention and tradition. Yes, I love to read about such-and-such author, restaurant, or popular space and plan ahead, if possible.

I am more of an eater than a cook. My ideal dinner party would be fresh oysters as an entrée (I love them, but it’s hard to get them to your home table), gazpacho soup (my grandfather’s recipe) or creamed corn with chipotle splashes depending on the weather, artichokes eaten leaf by leaf with a delicate vinaigrette, and roast beef with potato purée. And dulce de zapote negro for dessert; zapote negro is a seasonal tropical fruit whose black pulp mashed with orange juice into a velvety purée is heavenly. Of course, red wine. Ribera del Duero.

Q: What cultural offerings or trends have recently captured your attention?

A: I like what is happening with flamenco music and dance, moving it from the folkloric spots or touristic expectations to a more contemporary proposal where the depth and strength of the music and dance are pivotal. The fusion of Latin rhythms is very alive—C. Tangana, for example.

Q: You live in Mexico City. Can you share a few favorite spots?

A: The Cultural Center at Ciudad Universitaria where the volcanic landscape is mingled with the museums, music halls, and sculpture walkway is a grand open space in the south of my city. I never seem to get tired of the fountain in the central patio at the Museo Nacional de Antropología. The cantina La Flor de Valencia, where they serve snails in hot sauce on Thursdays, with its noise and tequilas. The San Jacinto sixteenth-century church in the heart of San Ángel, and just a few cobblestone streets ahead, the Casa del Risco fountain made of pieces of antique china is not to be missed. And, of course, Francisco Sosa Street in Coyoacán (the part of town where I live and grew up) with its vestiges of colonial mansions and centennial trees.

Q: We seem to be caught in a pile-up of bad news. On the darkest days, what picks you up?

A: A glass or two of red wine, not merlot, and Billie Holiday or Nina Simone, and then after the sadness, sevillanas, which I love to dance. And my three-year-old grandson, of course, asking beautiful questions and being loving and lovable.