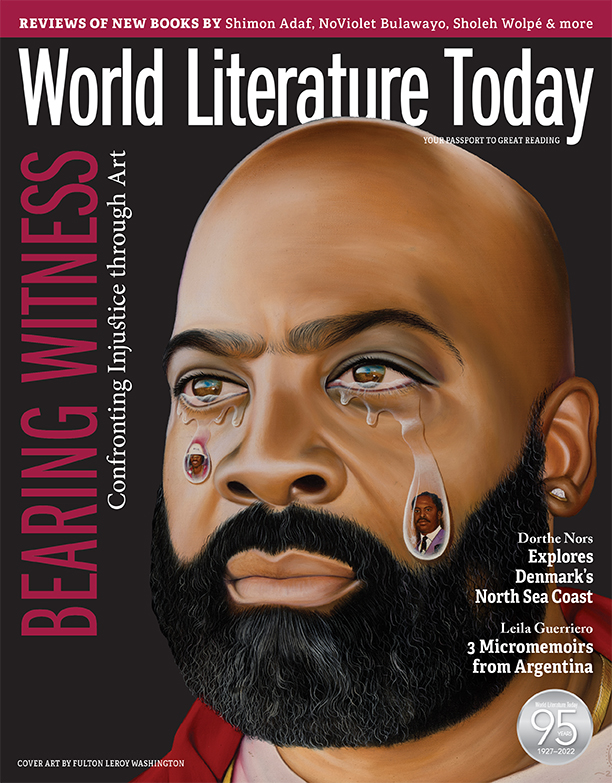

Notes for a Paleface Museum

Only I never came back

I was not going to be long

—W. S. Merwin

1

I live where Lady Gaga files her taxes

where the police

do as they please

where this paleface multitude

carries on breeding

because nobody calls

the social services you know thanks to the movies

to take away those kids

they’ve raised under a gaslight

on pills of passive-aggression and supremacies

for childhood was invented

for kids as blond as idiot hatchlings

who don’t know what to do in a world

where they are not the center of gravity

years after they were called upon to rule

and stick their hands under the wall.

2

Sometimes I walk around the track at your elementary school

I hold tight to headphones and sunscreen

and I imagine myself going back

and ending up mad with mamá’s madness

and papá and I grilling up possums and pigeons

and us dying like some splendid assholes

and I thank you for the vacation.

3

I will scream like the crows

pick up feathers

put black dead birds in the freezer

the thing is these people

have never come across a true mystic

someone who spits blood

and knows how to fill out the form after an autopsy

like a fox who has read over four books

and seven coffee grounds

someone who has indeed cooked toads

and holds the billy goat’s key

meanwhile they go buy trinkets at ethnic markets

and remind you that they voted for Obama

before Obama was even born.

4

Sometimes I think my husband

was lost in the woods as a boy,

that they murdered him on one of those adventures

with his Boy Scout troop

sometimes I think they took him and that this,

what they returned to me, or rather

what I scraped up with a spatula

is a shot that punctures, lands

and hides in a cicada carcass.

5

Everything is racial for the gringos

even making you feel guilty

for not knowing how to drive

just when they needed it the most

the gringos only know how to think

in terms of customer service.

6

I don’t know why we’re surprised that white people are racist.

Have you seen how they treat each other?

They live in a lonesome sarcasm contest

to claim they’re the most brilliant of the litter

they set the scene as if being considered

for a screenwriting job

on an edgy A24 comedy

and tear each other apart

with the same psychopathic half-smile

they wear when they hold the door for you

and still you go pretty far

then they’re surprised when their kids

don’t visit

shoot cocaine up their ass

or pick up a rifle and go down in history as another school shooting.

7

I’m calling my next cat Cardiac Arrest

and he will be the bearer of my dreams of late in which I die childless

alone in a hospital for second-class humans like myself

whether or not they crossed the border on horseback

because the horse is something that you bear inside yourself, I mean.

8

I need papers to cease to exist

like my greatest inaccuracy

I need to measure

my life in spoonfuls of melatonin

a border is a border is a border

I want to hold this landscape in my hand

it is papá before the sniveling

it is papá full of hope and feathers

because he supposed I’d be successful

and not die crossing sniffing sorting out some line

I was the party

learning to reclaim my monster in two tenses

but who knows

sometimes

I can barely breathe

and the task of staying alive leaves me blind.

Translation from the Spanish

Co-Translators’ Notes

by Jenna Tang & Arthur Malcolm Dixon

Translating across Borders

by Jenna Tang

Translating Enza García Arreaza’s poems, to me, is an act of activism. The more I decipher the language of hers, the more I feel seen.

As a translator and writer who grew up in Taiwan, a place that is still unfamiliar to many English speakers, there are views about America—especially views about racism in America—that are shared not only by Taiwanese people but also by the internationals who are looking at America from different sides. What makes our cultures so unseen, once we step out of home? Why is there a hierarchy of our rights to express ourselves, or to even exist on this side of the world?

Every culture has its own identity. Coming from one place never means coming from one culture only. We are all hopes and dreams together looking for a place to speak, to scream, and to live. Every individual exists with a diversity of cultural experiences, be they regional or widely international. Diversity is a thought kept within us that connects us with one another. Our stories matter, and the merciless reality of our stories having to coexist with white supremacy and power dynamics makes it ever more important to speak up, to show who we are, and that’s the energy I felt while translating Enza’s “Notes for a Paleface Museum.”

Enza speaks boldly about American whiteness. She speaks about the emotional impact of self, having to carry our stories while attempting to live in a new place that is not always welcoming to us. How do we perceive the idea of “border” now? What are borders for? Can borders exist while diversity seeks to thrive? This is a series of daring verses that spark great conversations. I feel honored to have the opportunity to translate Enza’s work and to share my perception of these topics with my co-translator Arthur Malcolm Dixon.

“Coming from one place never means coming from one culture only.” —Jenna Tang

False Universals

by Arthur Malcolm Dixon

Translating “Notes for a Paleface Museum” put me in a position as a translator that is unhealthily uncommon: it brought me face-to-face with my whiteness.

The predominant whiteness of literary translation into English is thankfully beginning to fade, as is evidenced by the work of my talented co-translator Jenna Tang and many others. But it is still the norm for white translators like me to bring writing from other languages into English.

This is not inconsequential. Our whiteness tends to lull us into a false sense of universality. We have the privilege of seeing ourselves as the standard—the etymologically apt “blank slate” whose blankness makes it the ideal transmitter of foreign speech. But, as Enza García Arreaza suggests in this poem, whiteness comes with its own distinctions, expectations, prerogatives, and pathologies. The circumstances of our birthplace, race, first language, and so on are just as relevant to our practices as they would be to any other translator’s. This does not mean white translators shouldn’t translate authors of color, but it does mean we should think, while translating, about our place in the world and how this place may differ from that of the author at hand.

“Our whiteness tends to lull us into a false sense of universality.” —Arthur Malcolm Dixon

Translating Enza’s poem, this was not optional. She addresses whiteness directly and white people anthropologically—a taste of our own medicine sans spoonful of sugar. It would be impossible to translate this poem without thinking about whiteness from without. It demands that its translator see white people as “they” rather than “we.”

This is good for us. I see all translation, literary or otherwise, as a pursuit of empathy, and empathy demands that we look in at ourselves from the outside. I’m thankful to Enza for this chance to pursue empathy as one only can through translation, and to Jenna for sharing it with me.