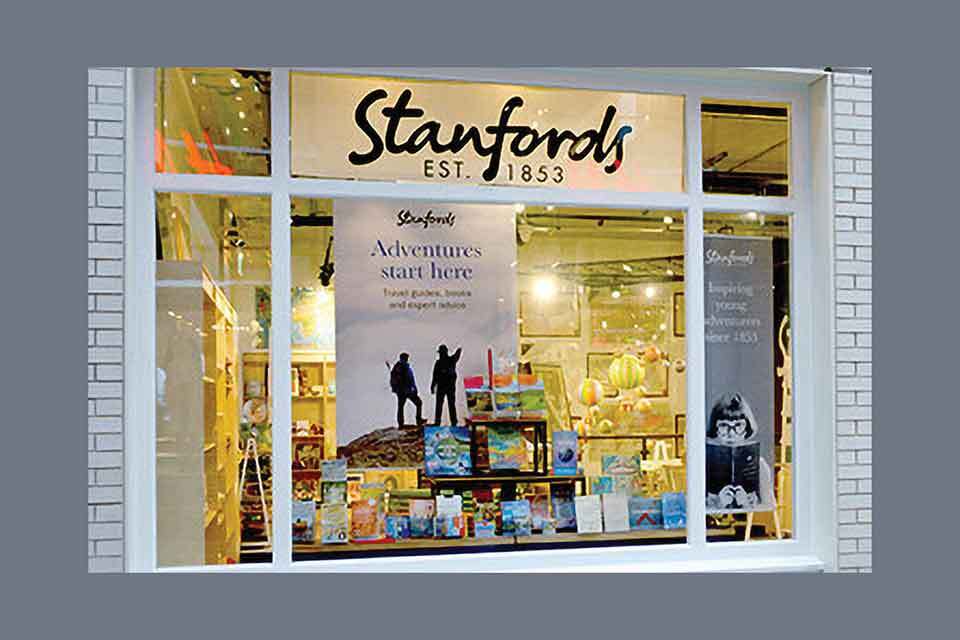

Stanfords London

AS A GENERAL RULE rule, I’m happiest in the countryside. The noise, the crush, the speed of cities, even the middling ones, frighten me, anger me, send me into a downward spiral, all in equal parts. I always find it strange, then, to feel so comfortable in London. Of course, get on the wrong street and the opposite is true, the city showing its narcissistic side and needing to remind you where you are every fifty feet. And traffic has destroyed what remained of classical London, as it has destroyed almost everything good on the earth. But there are times when one can fool oneself into believing otherwise, when the city is as quiet as a provincial hamlet, its wide streets empty except for a few dawdling pedestrians. It’s not the monuments but the lanes and alleys that make London what it is, which has “a roost for every bird,” as local writer Benjamin Disraeli had it.

London is a low city, nestled into the Thames Valley. Climb Primrose Hill, only 219 feet above sea level, and you’ll find it spread below you in its entirety. Wide as that spread is—some thirty-five miles across—I find London a good city for walking. The miles (and miles) dissolve as you draw up to one landmark after another: Dr. Samuel Johnson’s house; the terrace on Grafton where José de San Martín, the liberator of Peru, stayed during an 1811 visit; Savile Row, where tailors measure and cut cloth in the windows, just as they did in ’69 when the Beatles played through their last set from the rooftop of Number 3.

In that spirit, and anticipating my visit, I turned to Paul McCartney and Wings’ 1978 record London Town. “Walking down the sidewalk on a purple afternoon, I was accosted by a barker playing a simple tune upon his flute.” That was drumming through my head as I walked down Finchley Road, the beat interrupted by snatches of passing conversation, such as the man asking his mate, “So, you were saying about the detached retina?”

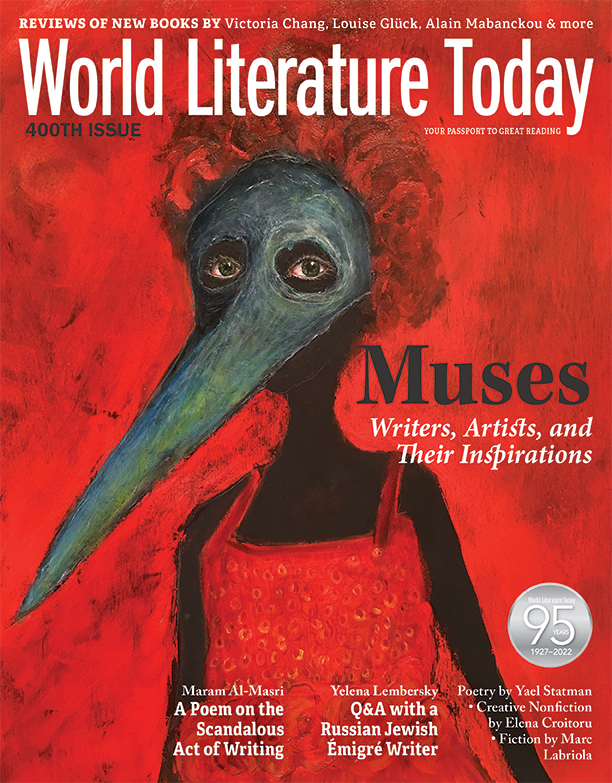

This is all color, a feeble swipe of a brush across a city whose paint never dries. It is but a moment, a London morning that is both irreplaceable and unrepeatable. Ostensibly, it is travel writing, a form that I find neither a genre nor a topic. Instead, I take Mary Wollstonecraft’s view that “the art of travel is only a branch of the art of thinking.” Nevertheless, travel writing was on my mind, as my destination was the shrine of that form, Stanfords bookshop.

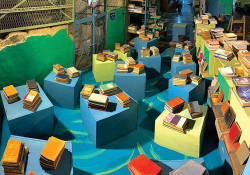

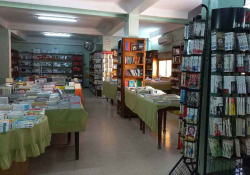

Traveling Brits have been visiting Stanfords, tucked away in the crook of Mercer Walk in Covent Garden, since 1853. Their basement full of maps supplied David Livingstone, Ernest Shackleton, and even Sherlock Holmes, who, in The Hound of the Baskervilles, sent Dr. Watson “down to Stanfords” to purchase a map of Dartmoor.

Just as those maps helped traveling Brits find their way out in the world, they also helped bring the world into focus; as those travelers journeyed widely, they wrote prolifically. What they put down wasn’t always correct, or sympathetic, or lyrical. But as a collection of an author’s remembrances and observations, travel books—perhaps more than other books—are an excellent reflection of a society within a time and place and history. What an author deems important is what she is conditioned to notice. Travel literature, then, makes a great marker from which to gauge changing sensibilities; through them, one can trace the course of how we have viewed the world. British writers, for instance: from the foppish jaunts of Evelyn Waugh (Remote People) through the hubristic record-seekers like Ranulph Fiennes (Living Dangerously), travel writing has become more personal and introspective. Now we have writers like Tharik Hussain contemplating Muslim Europe in Minarets in the Mountains and Cal Flyn, whose Islands of Abandonment looks for meaning in the absence of humanity. Travel literature seeks to blend the personal with the visible to create deep understanding of its subjects rather than a paper-thin diorama.

Outside again, the air was fresh and wet. Silver rain was falling down upon the dirty ground of London Town. Down an unceasing coil of steps, I descended into Covent Garden Underground. It was late, the station quiet. On the platform of this clay-bound capsule, a stranger held a single pink rose in a fold of paper. Her perfume turned the stale tunnel air into a floral zephyr. A drop of water wicked from the rose’s clipped stem and splashed upon the polished toe of her shoe. I whistled that familiar London Town tune: Someone, somewhere, has to know . . .