The Beauty and Importance of Our Names: A Conversation with Yejide Kilanko

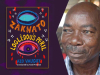

Among the shortlisted short stories for this year’s edition of the Caine Prize for African writing is Yejide Kilanko’s “This Tangible Thing,” which narrates a child’s journey of self-realization and self-affirmation. Kilanko is a Nigerian-born writer. Her debut novel, Daughters Who Walk This Path, a Canadian national best-seller, was longlisted for the 2016 Nigeria Prize for Literature. Her work includes a novella, Chasing Butterflies (2015), and two children’s picture books, There Is an Elephant in My Wardrobe (2019) and Juba and the Fireball (2020). Guernica Editions published her latest novel, A Good Name, in 2021. Kilanko’s short fiction is on Brittle Paper, Joyland, New Orleans Review, and Agbowó. A social worker, Kilanko and her family live in Ontario, where she works in child welfare and mental health. An avid Scrabble player, Kilanko is a health quality PhD student at Queen’s University in Canada. In this conversation, Darlington Chibueze Anuonye chats with Kilanko on the inspiration and aspiration of her story.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye: Congratulations on your Caine Prize shortlist recognition, Yejide. In your review of the works of writers of Nigerian descent who live in Canada, you celebrated their literary success by drawing attention to their inclusion in “the grand tapestry of Canadian literature” and their recognition by literary legitimating bodies like the Scotiabank Giller Prize. It is inspiring that you derive such pleasure in the promise of others. Now, I am wondering how do you feel about the Caine recognition?

Yejide Kilanko: Thank you, Darlington. I have been the recipient of great kindness, and I am happy when I get to celebrate other writers. In this beautiful moment for which I am grateful, I feel honored, delighted, and invigorated. While literary prizes do not define or legitimize a writer, the recognition they create widens possibilities. Those possibilities are invaluable to this writer committed to telling and sharing her stories for as long as possible.

Darlington: You deserve all the goodwill.

Yejide: Thanks. I don’t take what I get for granted.

Darlington: I think “This Tangible Thing” is a valuable lesson on the role of culture in therapy. Bíbíire’s ability to penetrate Àjọké’s mind and earn the girl’s friendship and trust is remarkable. She achieved, with her native wisdom, what the combined forces of the expertise of a therapist and the anxiety of Àjọké’s young parents could not do. I suppose there are lessons to learn from Bíbíire’s cultural approach to therapy.

Yejide: The story is more about the importance of love and engagement than culture. Due to their shared experience of selective mutism, Àjọké felt safe with her grandmother. When we feel safe with someone, we can afford to be vulnerable. The unconditional love Bíbíire offered her granddaughter fostered that necessary sense of freedom. No matter what kind of wisdom you have as a therapist, the truth is without a therapeutic relationship or alliance, you do not have a client. And without foundational trust between two people or within a group, there are no solid relationships.

Darlington: But the story is also full of history and culture. I have wondered, like Àjọké, why people do not often drown in their ancestral rivers, even if they have no swimming experience. So, I am thinking, just like her: Do rivers keep a database of everyone who has ancestry in the community they are domiciled?

Yejide: Knowing if ancestral rivers keep waterproof databases would be interesting. Your question did remind me of these words by the unforgettable Toni Morrison: “You know, they straightened out the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places. ‘Floods’ is the word they use, but in fact it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.” Perhaps, in their own ways, rivers hold onto pertinent information. As a nonswimmer, I am not visiting my village anytime soon to test the hypothesis.

Perhaps, in their own ways, rivers hold onto pertinent information.

Darlington: I’ll visit my village and ask. Whatever I find, I’ll share with you.

Yejide: Please do. That would make a great story.

Darlington: Your story deepened my knowledge about naming and its relationship to identity. I find that naming is a central element in the conception and development of your characters, as you told Uche Umezurike in an interview. I agree that names often hold and express the history and cultural heritage of the bearer. But isn’t it possible that beyond her classmate’s inability to distinguish between “Àjọké” and “a joke,” the bullying Àjọké experiences in school is a consequence of insouciant systemic racism, which derives from Western cultural parochialism or miseducation?

Yejide: Àjọké’s classmates knew the difference. Children mirror their environment, and systemic racism exists in schools. Years ago, I attended our local elementary school for kindergarten registration. The school secretary looked at my daughter’s Yoruba name, shook her head, and asked if my daughter had an English name. When I told her no, she said the Yoruba name would be hard for my daughter to spell. My four-year-old daughter was present, so she needed to hear that there was nothing wrong with her name. I smiled and told the secretary that if my daughter had to learn the twenty-six alphabet letters, she would also learn how to spell her twelve-letter name. There was no point telling her about the significant thought and prayers that went into choosing that name. When my daughter experienced numerous instances where her classmates were rude about her name, I countered those experiences by reinforcing its value. We must continue highlighting the beauty and importance of our names.

We must continue highlighting the beauty and importance of our names.

Darlington: I’m glad your daughter has a mother like you who sees well and insists on what is right.

Yejide: I was blessed to have had a mother who always encouraged me to use my voice.

Darlington: Great, blessings to your mother. “This Tangible Thing” is also an exercise in tenderness and healing. I am not referring to Bíbíire’s unmuting of Àjọké’s voice, the agency of self-affirmation she helped her to discover, significant as that is. I am speaking of the tender and therapeutic language in which the story is narrated. What does language mean to you, both as a therapist and as a writer?

Yejide: Whether verbal or nonverbal, language matters to me as a therapist and writer. During sessions, the words I say or choose not to say shape my conversations with clients. My prose follows a similar creation pattern. In this sense, language is a necessary vehicle. It takes me on a discovery journey and impacts the quality and length of the experience, either with my clients or readers.

Darlington: Àjọké’s grandfather was dead in the story yet a constant presence in the narrative. It’s so lovely how his wife remembers him. He even owned a camera Àjọké inherited. I know the short story has limited space to explore some characters fully, so I’d like to know, how do you imagine the man?

Yejide: As someone who has lost both parents, I know our loved ones maintain a constant presence even when physically gone. It was important to me that Àjọké also got to “meet” her grandfather. When I thought about Àjọké’s grandfather, I had imagined a man with a small stature and a bigger-than-life personality. In the story, I mentioned that his “tall, stiff cap sat at a rascally angle.” It was a nod to his playful persona. That playfulness attracted Bíbíire and kept her attention from the day he walked into her shop. The maps and the cameras left behind all pointed to a man interested in his world and wanting to capture it.

Darlington: When Àjọké and her father were about to return abroad, her father was worried about the weight of their luggage and even thought of leaving some things behind. He had similar worries when they arrived in the village because their luggage arrived a few days after. Does this say something about your immigrant experience?

Yejide: I left Nigeria for the first time in 2000 and didn’t return until five years later. I remember that our family of four had seven suitcases plus our hand luggage. Since I was a homemaker and we had limited income, I had been shopping during sale seasons for almost a year. I wanted to take something back for everyone. Those gifts are always expected from all those visiting home, even if their financial situation makes it challenging. Before leaving for Canada, I filled those suitcases with as much of home as I could, even though I knew that all perishable food items would eventually be eaten. For me, the luggage symbolizes the weight of unrealistic expectations from home, the weight of the love that keeps you committed to meeting them, and a heavy sense of displacement that makes you long for what is familiar amidst newness.

For me, the luggage symbolizes the weight of unrealistic expectations from home.

Darlington: Speaking of longing, on a recent Facebook post, you expressed your excitement about the possibility of meeting Warsan Shire at the Caine event in London. What would you tell her?

Yejide: I would go into fan-girl mode and gush to Warsan about how her poems have been a much-needed light for me. These long days need all the light we can get.

Darlington: Extend my love to her. Her poems keep me company often.

Yejide: I will.

Darlington: What are you writing now?

Yejide: I started a PhD program in September 2022, so I have been super focused on getting reacquainted with academic writing. It is a different lens. I hope that after my fall comprehensive exams, I can get back to editing my next picture book. Set in Nigeria, it is about a little boy living with dwarfism. I am also mentally teasing out ideas for another short story. That is all always fun.

Darlington: Best wishes on your studies and writing.

Yejide: Thank you.